EDIT 3 (2023-08-01): Recently I had to learn, that the “BrOSR” group of gamers, of which the below mentioned Jeffro is a member, does not only advocate interesting gaming concepts, but also political stances, I cannot approve of at all. If you want to learn more about these concerns, you might want to follow this post over on Tower of the Archmage. Well, maybe you don’t even want to follow the link, since it’s really not funny. I’m afraid the posts Archmage is referring to are no fabrications. Consequently I asked Jeffro to take down the link from his blog to my blog. I’ve never been part of the BrOSR, never will, and I don’t want to be associated with it in any way.

I’m happy, that the OSR and the ttrpg community in general is a creative, broad and diverse bunch, having fun with great games. Also my own interests don’t stop with rules-as-written old-school gaming. Life is colourful! Let’s embrace and celebrate diversity! Let’s be welcoming and share the fun!

With that out of the way, here is the original post:

So I took a deep dive into this rabbit hole for the last couple of weeks. Over on Mastodon user phf pointed me to a blog post by Jeffro on how to play Original D&D. Now, while somewhat polarizing, what Jeffro writes is intriguing. After I commented on one of his earlier post on How do you do Patron Style play in D&D, he answered with yet another blog post on the subject, clarifying some questions I had. So thanks Jeffro for this great inspiration! Consequentially these ideas led me to expand our current Traveller5 campaign to include High Level PCs (post in german).

Basically Jeffro suggests, that in a fantasy campaign, as it was originally conceived, experienced and played by the gaming groups of Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, the players do not only assume the roles of individual characters going on dungeon excursions, but also the roles of leaders, potentates and antagonists, with “the patrons”, i.e. the players who play these high level characters, given free hand to develop their dominions, and to make up their own agendas and strategies. Thus regular character parties will actually receive quests from, act on behalf of, or against high-level characters, who are in turn also controlled by players. In this kind of game the game master will act much more as a true referee than as a one-man-show puppeteer.

Recapitulating how the Old School Renaissance ventured to repopularize 1970s gaming style, Jeffro states:

“1:1 timekeeping with multiple independent domain-level actors is the fundamental axiom we have been missing.”

He goes on to describe, how by applying these two fundamental principles to his campaign, Jeffro observes how factions begin to act much more consistently and driven by intention, than could be simulated by a single game master, even with the help of various source materials and random tables. The reasons why this should work seem to be quite obvious and convincing to me.

Jeffro anticipates:

“your campaign will immediately begin spontaneously generating SECRETS as soon as you turn it on.”

And as from what I’ve experienced since adding patron style play to our Traveller5 campaign, I think I can confirm this expectation, and I will report on how this turned out in a future blog post.

If all of this sounds convincing to you, and you want to give it a go, I suggest you read Jeffro’s post The “Always On” Campaign, it’s a good place to start.

EDIT: Ben Milton of Questing Beast hast put out a great video about the same ideas.

EDIT 2: in the meantime I saw several videos about Robert Wardhaugh’s enormous D&D campaign. It’s been going on for 40 years. Apparently Robert also has domain level play going on. He refers to it as a macro component using war gaming rules, where players get to control tribes, realms and even whole nations and empires.

While “researching”, I’ve looked at quite a number of rules options to support domain level play. They’ve made it into their own blog post.

If you’re interested in my further thoughts on this subject, read on.

Domain-Level Play in the Original Games

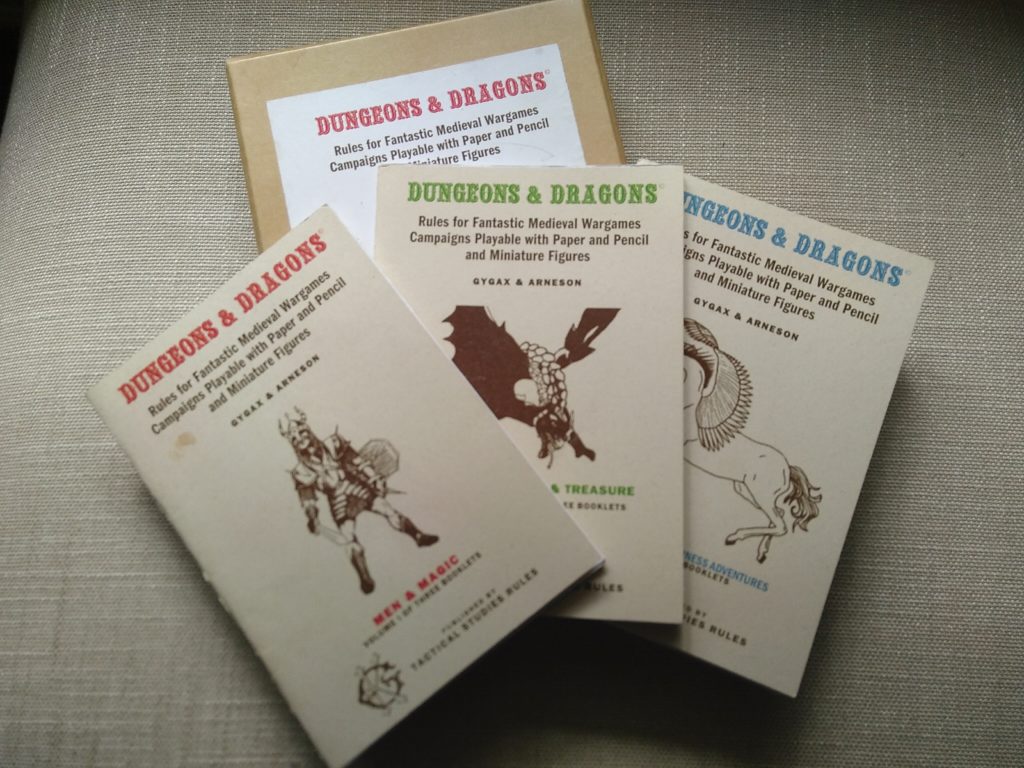

After reading all those blog posts, I went back to the original 1974 rules of the game. If domain level play should be the original assumption, the rules surely must contain some clue about it. Certainly there is a clue, but it’s not easy to find.

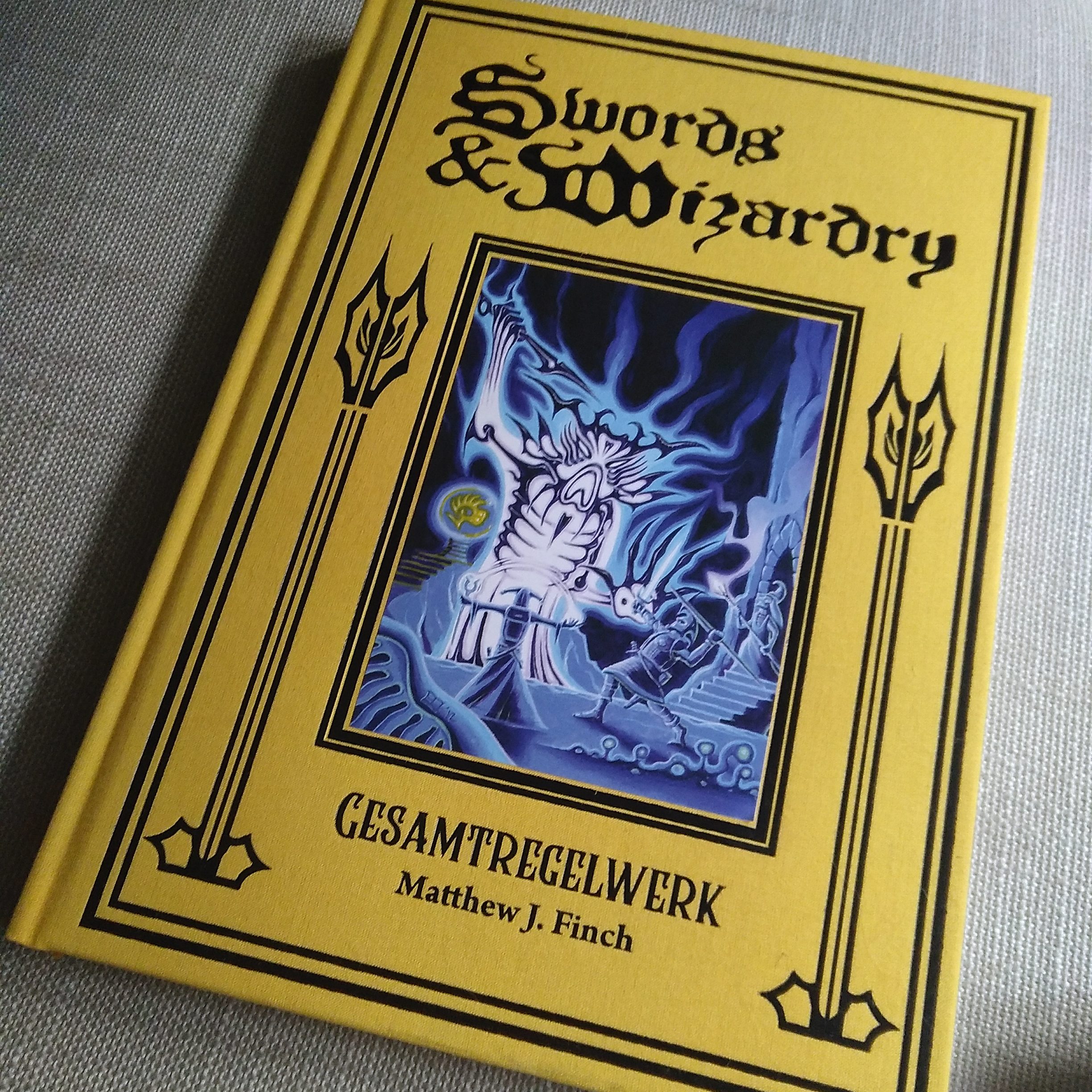

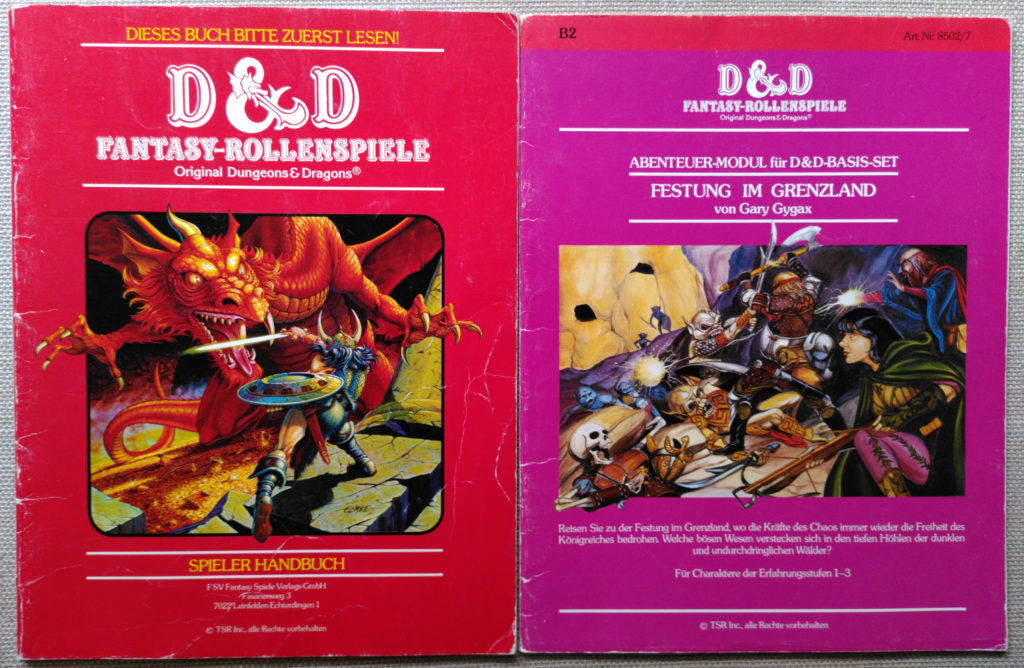

While there are rules about constructing castles and strongholds, ruling over baronies, cost of men at arms and so forth, I could not find any obvious mention, of what would be considered “patron style play” … not until I actually leant back, closed the booklet and looked at it’s subtitle: “Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns” … there it is, hiding in plain sight.

Considering all of the above, I think it fair to take said subtitle as an indication, that those rules were originally conceived as rules to be part of the set up, not necessarrily it’s only defining element. It has often been stated, that one reason, why the original three booklets seem to be difficult to understand in some places, is due to the authors being war gamers, writing for an audience of experienced war gamers. So it’s probably safe to say, that the basic assumption was the war game. And war games, naturally, are games of conflict simulation, in which players take up the roles of conflicting parties.

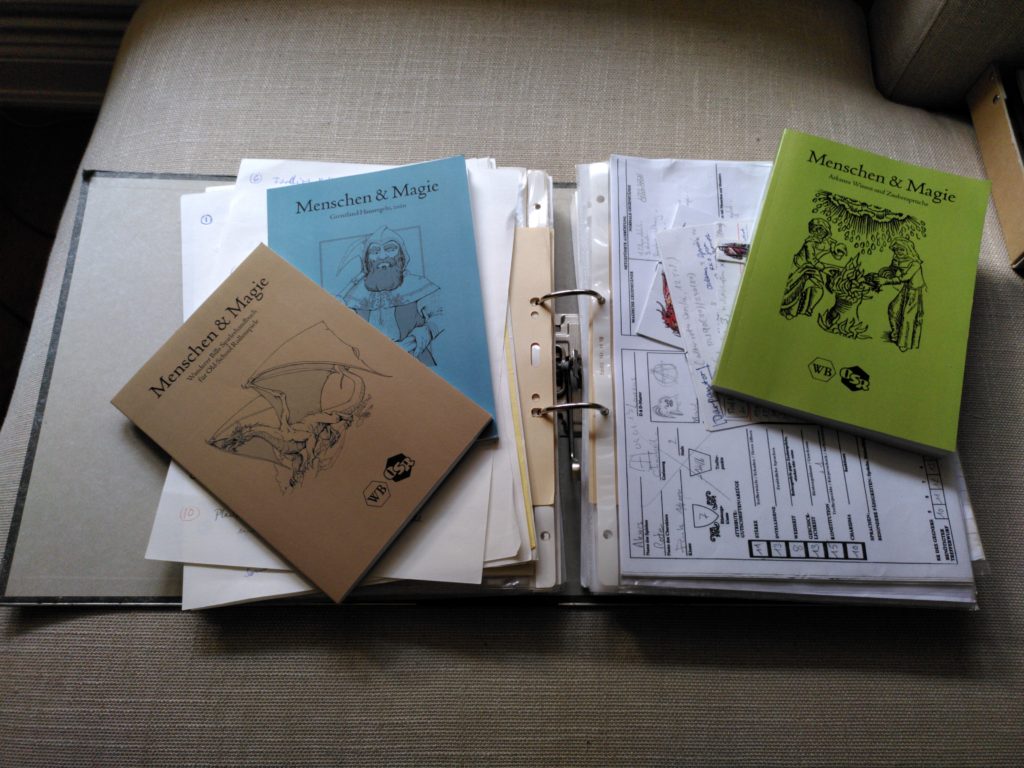

The first fantasy campaign, widely known as the Blackmoor campaign by Dave Arneson, and considered by many to be the origin of fantasy role playing games, started out in 1971 as a Braunstein game, set in a medieval fantasy setting. Braunstein in turn is a losely defined style of game, conceived by David Wesely in which players take up the roles of various allying or conflicting parties across a broad range of power levels from peasants to generals. Players are supposed to get information from the referee and act by giving written orders. As long as their characters are in the same location, their players may also communicate directly. While there seem to be no pubilshed rules for Braunstein, a lot can be inferred from published play reports and handouts.

In Secrets of Blackmoor, a documentary on the Blackmoor campaign, Stephen Rocheford, one of the original Blackmoor players states: “Yes, I am the High Priest of the Temple of the Frogs“. Clearly you don’t start out as a High Priest when you do conventional character creation in D&D. Obviously this was a patron player character, on which “Rocheford and Arneson [had] worked together to create this character as a humanoid alien with ties to extra terrestrial forces and technnology”.

The fact that in two of D&D’s most famous adventure modules B2 – Keep on the Borderlands, and T1 – The Village of Hommlet, not just the “monsters”, but also the “good non-player characters” are fleshed out with complete combat stats, has been commented on with some amusement, but in the light of an adversarial game being the default, this seems to actually make a lot of sense.

So, these findings seem to indicate, that domain level play might actually have been the default assumption. But there is more, if we look at games and adventure modules published after D&D hit the market.

Antagonistic play in other games

In the canon of Classic Traveller, there are two adventures, which I find quite remarkable with respect to patron style play. Namely Adventure 5 – Trillion Credit Squadron (1981), and Adventure 7 – Broadsword (1982). The former offers an elaborate frame work for setting up a game of conflicting space navies, with missions for individual characters mentioned only as a secondary possibility. The latter is a collection of scenarios designed around the crew and troops of a mercenary ship. The referee is given the advice to have some players play the antagonists, and instructions to stage the scenarios on large scale terrain maps. Similarly in Adventure 5 – Leviathan the referee is advised to have “the player party preferably […] occupy command posts”, giving the game a wholly different perspective, than that of the usual struggling adventurers.

Interestingly also the basic rules set of the Generic Universal Roleplaying System (GURPS) by Steve Jackson Games, contains rules and suggestions about adversarial players, albeit with the notion that an adversarial player will play adverseries ultimately designed by the game master.

And then, there is also Fate, a modern character focused, “story telling” game which, by treating every important story element as a character, offers rules and examples to play on a, possibly adversarial, faction or domain level. There are examples in the Fate Toolkit, as well as in the Burn Shift and Mindjammer settings by Sarah J. Newton.

I’m sure one could find many more examples. If you know of any, please add them to the comments!

The gentle but seldomly trodden path to domain level play

Of course I am perfectly aware, that Dungeons & Dragons’ actual rules put forth in the three brown booklets of 1974 do fokus on characters starting at low level, going on dungeon expeditions as the default setting. This primary focus of the game is again repeated in the paragraph THE FIRST DUNGEON ADVENTURE, in Gary Gygax’s 1979 Dungeon Masters Guide. And it has become the assumed standard ever since, with domain level play only starting once characters reach the lofty, so called “name level”.

Similarly in Traveller, patrons are usually considered to be non-player characters, who might offer jobs or quests to the player characters. And while Marc Miller writes “With time and a growing knowledge of the universe, the players themselves will develop their own missions and become for a time, their own patrons.”

From an educational perspective this gentler path to domain level play appears to be an easy, little demanding way to do it, but achieving patronage through play seems to happen rarely enough, and if at all, only after many sessions have been played.

While in this light, games which never reach domain level play might seem to be missing out, I don’t believe wargame like, adversarial, domain level play to be the end all and be all. Since the days of the old war gaming grognards, a lot of great developement has happend, and character driven role playing games have developed into a multitude of intersting genres and sub genres. Playing a well scripted 1920s pulp adventure may be a phenomenal experience, telling relationship driven stories in a postapocalyptic dystopia might be all you’ll ever want from this hobby. And heroic high fantasy as embodied by todays 5th edition of the original fantasy role playing game has become a whole genre of it’s own. If you like it, there’s nothing wrong with playing the game by it’s modern rules.

All this post is really about, is just say, that playing the game by it’s original rules, might offer an experience much more immersive, than you ever thought. And clearly those original rules sets contain those rules aimed at domain level play. They may just as well be applied right from the start — when you begin to plot your Grand Campaign!

More food for thought

- http://wanderinggamist.blogspot.com/2021/07/current-11-timescale-campaigns.html

- https://bdubsanddragons.blogspot.com/2021/07/acks-session-24-croc-whisperers.html

- https://waterdeeposr.blogspot.com/2021/06/real-time-play-braunstein-effect.html

Finally, be sure to watch Secrets of Blackmoor!